Archive format

This isn’t a new problem.

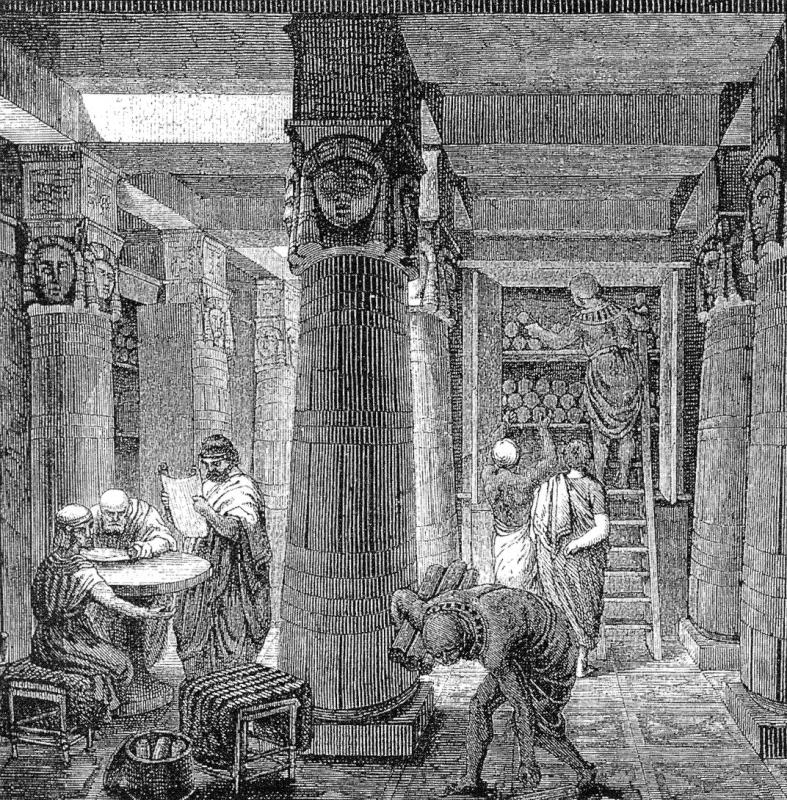

If you are going to archive something successfully you need a format that will be accessible for years to come. This is a fundamental concept of anticryptography. It goes way back also. The library of Alexandria was an immense effort that was made possible by a simple format, ink on sheets. They could copy anything that was written to new scrolls and store it away. A ship comes to port and a set of scribes run out and start scribbling. So long as that ship wasn’t some sort of scroll mobile or scroll store delivery it could be done before ship stores were loaded and unloaded.

In that, and many other cases, the base media of the format was some form of ink writing, probably on papyrus. It did not age well. It would dry out and come apart as it was unrolled and rolled back up with each use. Paper later fixed some of these issues. Both though proved to be hard to survive in fires and exposure to the elements. They lasted long enough that the language portion of the writings became a problem. As time went on the scrolls had to be copied by scribes and hopefully updated in linguistic terms before the older written meaning was lost.

Today

We have great paper, but our data has outstripped it as an option. Now we have to store things digitally. Those digital versions run around as files no matter the system or technology they are stored on. So long as we define a “file” as a sequence of bytes I think that part won’t change (watch bytes change on us as it did in the 60’s).

Surveying the landscape a few contenders come up for the most common format used today. There are of course specific formats for each type of media, but there are 2 that are still in large scale use for general collections. Those would be tar and zip.

Both formats offer ways for us to generically store piles of files in a structured hierarchy, and some limited metadata about them, in a single file. A meta file if you will. Why those 2 formats and not any of the others that have been around over time?

If we look at the other formats we can see a road littered with problems. The biggest competitor to tar was cpio. It was awkward to use and while both were first tape orientated, tar (short for tape archive) lent itself better to hard drives and other random access media. Maybe if we stored data in strands of DNA or something cpio would make sense, but we don’t. While Unix has had others over time tar has remained popular and useful.

Zip on the other hand is a sordid tale and one that proves a point.

The sordid tale of zip.

Long ago (roughly 1985) a company called System Enhancement Associates (SEA) released a free tool for archiving files called arc. It could gather up a bunch of files, compress them and spit out a single file that could be unpacked into the original set of files. They based their work on the ar tool that is frequently used to build libraries that can be linked against, but they made it more generic.

Before that point files were often compressed separately and copied from system to system in a loose bundle. Around that time the number of files increased in use and formats like this became popular in the PC world. At the same time the concepts of tapes started to migrate to files on larger systems and formats like tar emerged as we talked about above.

Arc was very popular and very successful. With SEA releasing the source code it took off like wild fire and was seen on almost every system in the 80’s. At that time it was on it’s way to becoming the one universal archival format. So what happened?

Greed

In 1986 Phil Katz of PKware put out a version of arc tools that were significantly faster. He hand coded some critical routines in Intel assembly for the IBM platform and split the 2 primary functions into 2 different programs so they stayed small. In the IBM PC world those small executables would run on machines with less RAM and that opened up the tools to more users. If this sounds odd, back then most PCs still came with 64K-256K of RAM and you added expensive cards to add RAM up to 640K (but who would ever need more :-) ).

SEA sued PKware over this as they saw their version being usurped. Since they had released the source code they had trouble in court. An independent reviewer of the source code employed by the court commented on how much was copied from arc to pkarc that even misspellings in the comments were often the same. SEA’s lawyers claimed that the format was what was owned. With that one legal move they doomed themselves forever.

Phil Katz came up with a new format and openly released the format specification while keeping the executable protected under copyright. The new format was called “zip” and it had a number of improvements. At that point the court case didn’t matter, the war was now between an open and proprietary format, and the open one won.

In the end that court case ended badly for all parties involved. SEA got out of shareware and was eventually sold. The original developer left software in disgust. While Phil Katz won, his alcoholism grew worse and he eventually died form it.

Zip everywhere

When Phil Katz released the open format of zip he started a wheel in motion that moves to this day. It was a capable format that worked on a range of systems (DOS/Windows, Unix and VMS as an example of range). Supporting directory structures, some simple metadata and better compression than the earlier arc format made it an instant success. What made it the format that is today though was that open format. Anyone could implement it and open source implementations could be linked into code as a standard file format.

Sure there were some limitations. The biggest was the reliance on signed 32 bit numbers that kept every aspect below 2GB in size. This wasn’t a limitation when it was released because no one had hardware that could handle 2GB files, but became one in the decade that followed. The open nature of zip made implementing a 64 bit version easy to do and adopt.

Many other formats have come along over time and some got popular. The rar format was very popular for some time, but it’s closed nature limited how far it went.

Hiding in plain sight.

Zip started to become the underlying format of many popular applications and delivery formats. Java distributes software in “jar” files that despite sounding like “tar” are really just zip files with a manifest file in it.

When Microsoft needed to make Office documents an open standard they switched components to XML files and threw them into a described directory hierarchy inside a zip file. You can unzip any of your Word, Excel or Powerpoint files and walk through it by hand. I’ve also written scripts that parse and alter those formats to achieve simple and easy results. This was way easier than the earlier Office file formats that used an emulated floppy disk to store everything.

The list doesn’t stop with those 2 massive examples. Reading and writing zip files is available in every popular programming language and considered so common it is part of the standard library of some modern ones. Python makes it very easy to work with as part of the standard library as does Golang.

Moving forward

The definition of the zip file format is still driven by PKware and they have not been sitting on their laurels. In this year they added the Zstandard compression method which is ideal for small files and good overall performance. While it would be better in the long term to have an open process, this one has worked so far. If PKware goes away or changes to a closed format the last open one could be extended by a larger community for years to come.

While the format is not ideal in an anticryptography sense, I think it is a good one to use for long term archiving data right now. The format is well documented and easy to understand. Software to read it is almost everywhere and can be easily ported for decades to come. I would feel comfortable that an archivist in a 100 years could work with a zip file easily. I wouldn’t be surprised if the general public still found them painless to open in that time either.

I don’t see any other format in common use today that can meet all of that. Tar has been around longer and is arguably better designed, but compression is layered and software to read it isn’t quite as common. The hdf format is better designed for doing interesting things at a higher performance but isn’t as easy to work with. Zip is the best format for long term archiving until we purpose build a better one.